Construction on vivaNext projects is moving full speed ahead. As structures are built and roads are widened, visions of the future are becoming a reality. The promise of the next generation of York Region’s rapid transit is coming to life.

Here at the vivaNext office, we have also welcomed a next generation, with two new summer students joining our communications team. They both have grown up in York Region, one hailing from Newmarket while the other is from Vaughan. Each of them has lived in the Region for over twenty years, so they know how it has changed over time. Both are looking forward to being a part of the team that brings York Region into its next era.

I hope that excitement like this spreads to all generations. I see the vivaNext generation as people of all ages, who use the vivaNext transit system as a way to travel to modern, urban destinations inside and outside of York Region.

For people in Vaughan, the Vaughan Metropolitan Centre (or VMC) will be a new downtown. As a hub for transit, business, shopping, and recreation, the VMC will offer a site for all ages to come together and experience York Region. Our summer student, Alanna, mentioned that she is thrilled about the opportunity to have a “downtown experience” closer to home.

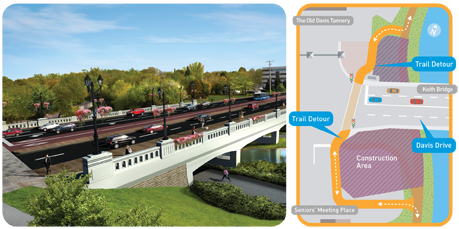

John, our summer student from Newmarket, is looking forward to a highly improved Davis Drive for York Region residents. With pedestrian-friendly boulevards and easy access to places to shop, work, and relax, Davis Drive will become a new destination for the next generation of vivaNext travellers.

Taken together, these individual projects connect into the vivaNext plan for a seamless rapid transit network, making it easy to travel to work, shopping destinations, and recreation.

Our projects will benefit everyone who lives or works in York Region, and we want to keep in touch with all of you as these projects are underway. We’re making sure residents are in-the-know with our constant social media updates Be sure to follow us on Twitter and Facebook, and sign up for our e-mail updates.

The future is bright, and the vivaNext generation of travellers has a lot to be excited about.

[poll id=”31″]